In a near-future war—one which may begin tomorrow, for all we all know—a soldier takes up a shooting position on an empty rooftop. His unit has been fighting through the town block by block. It feels as if enemies could possibly be lying in silent wait behind every corner, able to rain fire upon their marks the moment they’ve a shot.

Through his gunsight, the soldier scans the windows of a close-by constructing. He notices fresh laundry hanging from the balconies. Word is available in over the radio that his team is about to maneuver across an open patch of ground below. As they head out, a red bounding box appears in the highest left corner of the gunsight. The device’s computer vision system has flagged a possible goal—a silhouetted figure in a window is drawing up, it seems, to take a shot.

The soldier doesn’t have a transparent view, but in his experience the system has a superhuman capability to select up the faintest tell of an enemy. So he sets his crosshair upon the box and prepares to squeeze the trigger.

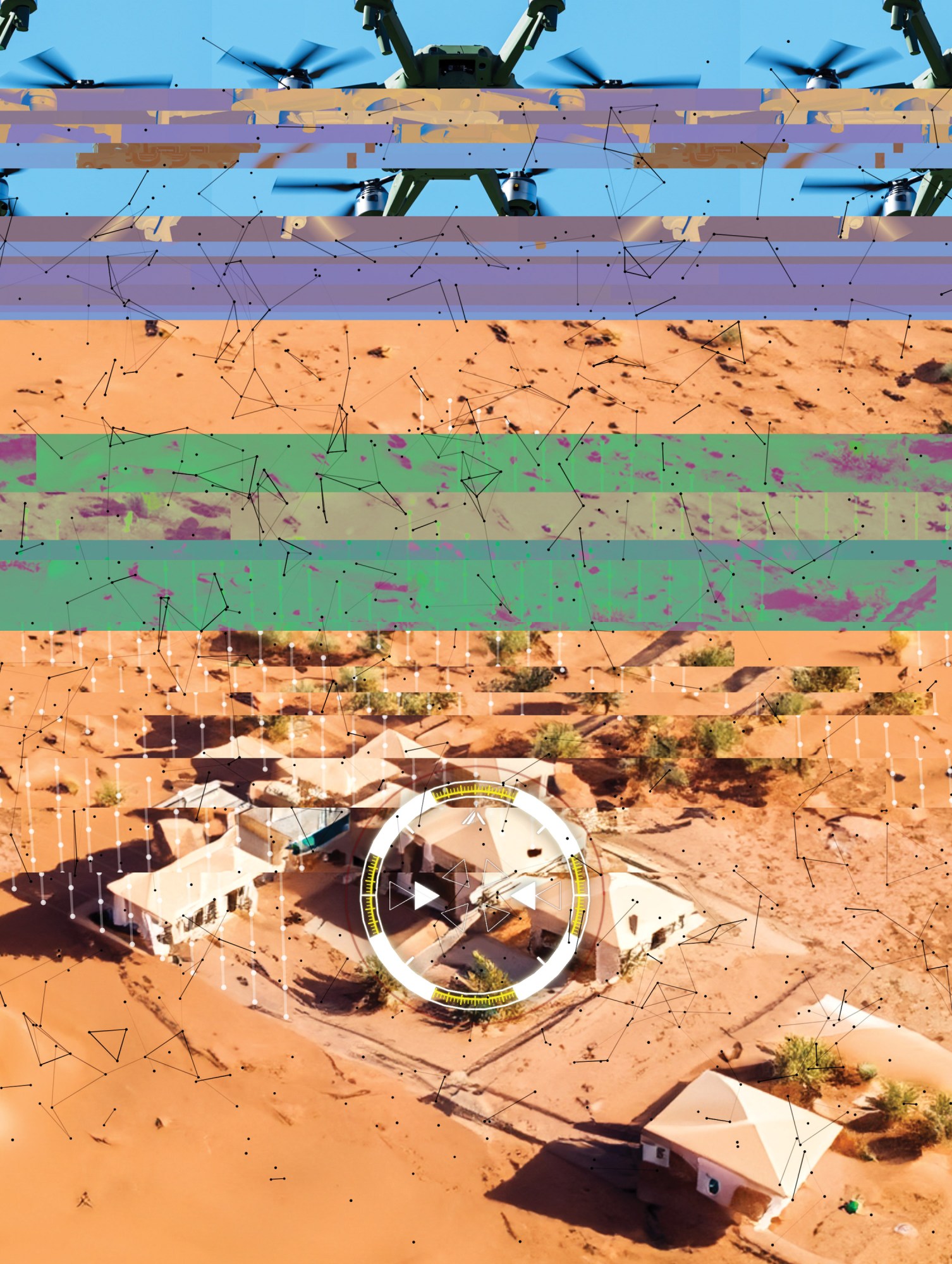

In several war, also possibly just over the horizon, a commander stands before a bank of monitors. An alert appears from a chatbot. It brings news that satellites have picked up a truck entering a certain city block that has been designated as a possible staging area for enemy rocket launches. The chatbot has already advised an artillery unit, which it calculates as having the best estimated “kill probability,” to take aim on the truck and stand by.

In response to the chatbot, not one of the nearby buildings is a civilian structure, though it notes that the determination has yet to be corroborated manually. A drone, which had been dispatched by the system for a better look, arrives on scene. Its video shows the truck backing right into a narrow passage between two compounds. The chance to take the shot is rapidly coming to an in depth.

For the commander, every thing now falls silent. The chaos, the uncertainty, the cacophony—all reduced to the sound of a ticking clock and the sight of a single glowing button:

“APPROVE FIRE ORDER.”

To drag the trigger—or, because the case could also be, not to tug it. To hit the button, or to carry off. Legally—and ethically—the role of the soldier’s decision in matters of life and death is preeminent and indispensable. Fundamentally, it’s these decisions that outline the human act of war.

It must be of little surprise, then, that states and civil society have taken up the query of intelligent autonomous weapons—weapons that may select and fire upon targets with none human input—as a matter of significant concern. In May, after near a decade of discussions, parties to the UN’s Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons agreed, amongst other recommendations, that militaries using them probably have to “limit the duration, geographical scope, and scale of the operation” to comply with the laws of war. The road was nonbinding, nevertheless it was no less than an acknowledgment that a human has to play an element—somewhere, sometime—within the immediate process leading as much as a killing.

But intelligent autonomous weapons that fully displace human decision-making have (likely) yet to see real-world use. Even the “autonomous” drones and ships fielded by the US and other powers are used under close human supervision. Meanwhile, intelligent systems that merely guide the hand that pulls the trigger have been gaining purchase within the warmaker’s tool kit. They usually’ve quietly change into sophisticated enough to lift novel questions—ones which might be trickier to reply than the well-covered wrangles over killer robots and, with each passing day, more urgent: What does it mean when a call is simply part human and part machine? And when, if ever, is it ethical for that call to be a call to kill?

For a very long time, the concept of supporting a human decision by computerized means wasn’t such a controversial prospect. Retired Air Force lieutenant general Jack Shanahan says the radar on the F4 Phantom fighter jet he flew within the Eighties was a call aid of sorts. It alerted him to the presence of other aircraft, he told me, in order that he could work out what to do about them. But to say that the crew and the radar were coequal accomplices can be a stretch.

That has all begun to vary. “What we’re seeing now, no less than in the best way that I see this, is a transition to a world [in] which it’s good to have humans and machines … operating in some form of team,” says Shanahan.

The rise of machine learning, particularly, has set off a paradigm shift in how militaries use computers to assist shape the crucial decisions of warfare—as much as, and including, the last word decision. Shanahan was the primary director of Project Maven, a Pentagon program that developed goal recognition algorithms for video footage from drones. The project, which kicked off a brand new era of American military AI, was launched in 2017 after a study concluded that “deep learning algorithms can perform at near-human levels.” (It also sparked controversy—in 2018, greater than 3,000 Google employees signed a letter of protest against the corporate’s involvement within the project.)

With machine-learning-based decision tools, “you could have more apparent competency, more breadth” than earlier tools afforded, says Matt Turek, deputy director of the Information Innovation Office on the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. “And maybe an inclination, consequently, to show over more decision-making to them.”

A soldier looking out for enemy snipers might, for instance, accomplish that through the Assault Rifle Combat Application System, a gunsight sold by the Israeli defense firm Elbit Systems. In response to an organization spec sheet, the “AI-powered” device is able to “human goal detection” at a spread of greater than 600 yards, and human goal “identification” (presumably, discerning whether an individual is someone who could possibly be shot) at in regards to the length of a football field. Anna Ahronheim-Cohen, a spokesperson for the corporate, told MIT Technology Review, “The system has already been tested in real-time scenarios by fighting infantry soldiers.”

One other gunsight, built by the corporate Smartshooter, is advertised as having similar capabilities. In response to the corporate’s website, it may well even be packaged right into a remote-controlled machine gun just like the one which Israeli agents used to assassinate the Iranian nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh in 2021.

Decision support tools that sit at a greater remove from the battlefield might be just as decisive. The Pentagon appears to have used AI within the sequence of intelligence analyses and decisions leading as much as a possible strike, a process often called a kill chain—though it has been cagey on the main points. In response to questions from MIT Technology Review, Laura McAndrews, an Air Force spokesperson, wrote that the service “is utilizing a human-machine teaming approach.”

The range of judgment calls that go into military decision-making is vast. And it doesn’t all the time take artificial super-intelligence to dispense with them by automated means.

Other countries are more openly experimenting with such automation. Shortly after the Israel-Palestine conflict in 2021, the Israel Defense Forces said it had used what it described as AI tools to alert troops of imminent attacks and to propose targets for operations.

The Ukrainian army uses a program, GIS Arta, that pairs each known Russian goal on the battlefield with the artillery unit that’s, in response to the algorithm, best placed to shoot at it. A report by The Times, a British newspaper, likened it to Uber’s algorithm for pairing drivers and riders, noting that it significantly reduces the time between the detection of a goal and the moment that concentrate on finds itself under a barrage of firepower. Before the Ukrainians had GIS Arta, that process took 20 minutes. Now it reportedly takes one.

Russia claims to have its own command-and-control system with what it calls artificial intelligence, nevertheless it has shared few technical details. Gregory Allen, the director of the Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies and certainly one of the architects of the Pentagon’s current AI policies, told me it’s necessary to take a few of these claims with a pinch of salt. He says a few of Russia’s supposed military AI is “stuff that everybody has been doing for a long time,” and he calls GIS Arta “just traditional software.”

The range of judgment calls that go into military decision-making, nonetheless, is vast. And it doesn’t all the time take artificial super-intelligence to dispense with them by automated means. There are tools for predicting enemy troop movements, tools for determining easy methods to take out a given goal, and tools to estimate how much collateral harm is prone to befall any nearby civilians.

None of those contrivances could possibly be called a killer robot. However the technology just isn’t without its perils. Like all complex computer, an AI-based tool might glitch in unusual and unpredictable ways; it’s not clear that the human involved will all the time have the ability to know when the answers on the screen are right or incorrect. Of their relentless efficiency, these tools may additionally not leave enough time and space for humans to find out if what they’re doing is legal. In some areas, they might perform at such superhuman levels that something ineffable in regards to the act of war could possibly be lost entirely.

Eventually militaries plan to make use of machine intelligence to stitch a lot of these individual instruments right into a single automated network that links every weapon, commander, and soldier to each other. Not a kill chain, but—because the Pentagon has begun to call it—a kill web.

In these webs, it’s not clear whether the human’s decision is, actually, very much of a call in any respect. Rafael, an Israeli defense giant, has already sold one such product, Fire Weaver, to the IDF (it has also demonstrated it to the US Department of Defense and the German military). In response to company materials, Fire Weaver finds enemy positions, notifies the unit that it calculates as being best placed to fireside on them, and even sets a crosshair on the goal directly in that unit’s weapon sights. The human’s role, in response to one video of the software, is to choose from two buttons: “Approve” and “Abort.”

Let’s say that the silhouette within the window was not a soldier, but a baby. Imagine that the truck was not delivering warheads to the enemy, but water pails to a house.

Of the DoD’s five “ethical principles for artificial intelligence,” that are phrased as qualities, the one which’s all the time listed first is “Responsible.” In practice, which means when things go incorrect, someone—a human, not a machine—has got to carry the bag.

In fact, the principle of responsibility long predates the onset of artificially intelligent machines. All of the laws and mores of war can be meaningless without the basic common understanding that each deliberate act within the fight is all the time on But with the prospect of computers taking over all manner of sophisticated latest roles, the age-old precept has newfound resonance.

Of the Department of Defense’s 5 “ethical principles for artificial intelligence,” that are phrased as qualities, the one which’s all the time listed first is “Responsible.”

“Now for me, and for most individuals I ever knew in uniform, this was core to who we were as commanders: that anyone ultimately shall be held responsible,” says Shanahan, who after Maven became the inaugural director of the Pentagon’s Joint Artificial Intelligence Center and oversaw the event of the AI ethical principles.

That is why a human hand must squeeze the trigger, why a human hand must click “Approve.” If a pc sets its sights upon the incorrect goal, and the soldier squeezes the trigger anyway, that’s on the soldier. “If a human does something that results in an accident with the machine—say, dropping a weapon where it shouldn’t have—that’s still a human’s decision that was made,” Shanahan says.

But accidents occur. And that is where things get tricky. Modern militaries have spent lots of of years determining easy methods to differentiate the unavoidable, blameless tragedies of warfare from acts of malign intent, misdirected fury, or gross negligence. Even now, this stays a difficult task. Outsourcing an element of human agency and judgment to algorithms built, in lots of cases, across the mathematical principle of optimization will challenge all this law and doctrine in a fundamentally latest way, says Courtney Bowman, global director of privacy and civil liberties engineering at Palantir, a US-headquartered firm that builds data management software for militaries, governments, and huge firms.

“It’s a rupture. It’s disruptive,” Bowman says. “It requires a brand new ethical construct to have the ability to make sound decisions.”

This 12 months, in a move that was inevitable within the age of ChatGPT, Palantir announced that it’s developing software called the Artificial Intelligence Platform, which allows for the combination of enormous language models into the corporate’s military products. In a demo of AIP posted to YouTube this spring, the platform alerts the user to a potentially threatening enemy movement. It then suggests that a drone be sent for a better look, proposes three possible plans to intercept the offending force, and maps out an optimal route for the chosen attack team to achieve them.

And yet even with a machine able to such apparent cleverness, militaries won’t want the user to blindly trust its every suggestion. If the human presses just one button in a kill chain, it probably shouldn’t be the “I imagine” button, as a concerned but anonymous Army operative once put it in a DoD war game in 2019.

In a program called Urban Reconnaissance through Supervised Autonomy (URSA), DARPA built a system that enabled robots and drones to act as forward observers for platoons in urban operations. After input from the project’s advisory group on ethical and legal issues, it was decided that the software would only ever designate people as “individuals of interest.” Although the aim of the technology was to assist root out ambushes, it might never go to date as to label anyone as a “threat.”

This, it was hoped, would stop a soldier from jumping to the incorrect conclusion. It also had a legal rationale, in response to Brian Williams, an adjunct research staff member on the Institute for Defense Analyses who led the advisory group. No court had positively asserted that a machine could legally designate an individual a threat, he says. (Nevertheless, he adds, no court had specifically found that it might be illegal, either, and he acknowledges that not all military operators would necessarily share his group’s cautious reading of the law.) In response to Williams, DARPA initially wanted URSA to have the ability to autonomously discern an individual’s intent; this feature too was scrapped on the group’s urging.

Bowman says Palantir’s approach is to work “engineered inefficiencies” into “points within the decision-making process where you really do wish to slow things down.” For instance, a pc’s output that points to an enemy troop movement, he says, might require a user to hunt down a second corroborating source of intelligence before proceeding with an motion (within the video, the Artificial Intelligence Platform doesn’t appear to do that).

“If people of interest are identified on a screen as red dots, that’s going to have a unique subconscious implication than if people of interest are identified on a screen as little glad faces.”

Rebecca Crootof, law professor on the University of Richmond

Within the case of AIP, Bowman says the concept is to present the data in such a way “that the viewer understands, the analyst understands, this is simply a suggestion.” In practice, protecting human judgment from the sway of a beguilingly smart machine could come right down to small details of graphic design. “If people of interest are identified on a screen as red dots, that’s going to have a unique subconscious implication than if people of interest are identified on a screen as little glad faces,” says Rebecca Crootof, a law professor on the University of Richmond, who has written extensively in regards to the challenges of accountability in human-in-the-loop autonomous weapons.

In some settings, nonetheless, soldiers might only want an “I imagine” button. Originally, DARPA envisioned URSA as a wrist-worn device for soldiers on the front lines. “Within the very first working group meeting, we said that’s not advisable,” Williams told me. The sort of engineered inefficiency mandatory for responsible use just wouldn’t be practicable for users who’ve bullets whizzing by their ears. As an alternative, they built a pc system that sits with a dedicated operator, far behind the motion.

But some decision support systems are definitely designed for the sort of split-second decision-making that happens right within the thick of it. The US Army has said that it has managed, in live tests, to shorten its own 20-minute targeting cycle to twenty seconds. Nor does the market appear to have embraced the spirit of restraint. In demo videos posted online, the bounding boxes for the computerized gunsights of each Elbit and Smartshooter are blood red.

Other times, the pc shall be right and the human shall be incorrect.

If the soldier on the rooftop had second-guessed the gunsight, and it turned out that the silhouette was actually an enemy sniper, his teammates could have paid a heavy price for his split second of hesitation.

That is a unique source of trouble, much less discussed but no less likely in real-world combat. And it puts the human in something of a pickle. Soldiers shall be told to treat their digital assistants with enough mistrust to safeguard the sanctity of their judgment. But with machines which might be often right, this same reluctance to defer to the pc can itself change into some extent of avertable failure.

Aviation history has no shortage of cases where a human pilot’s refusal to heed the machine led to catastrophe. These (often perished) souls haven’t been looked upon kindly by investigators searching for to elucidate the tragedy. Carol J. Smith, a senior research scientist at Carnegie Mellon University’s Software Engineering Institute who helped craft responsible AI guidelines for the DoD’s Defense Innovation Unit, doesn’t see a difficulty: “If the person in that moment feels that the choice is incorrect, they’re making it their call, they usually’re going to need to face the results.”

For others, it is a wicked ethical conundrum. The scholar M.C. Elish has suggested that a human who’s placed in this sort of unimaginable loop could find yourself serving as what she calls a “moral crumple zone.” Within the event of an accident—no matter whether the human was incorrect, the pc was incorrect, or they were incorrect together—the one who made the “decision” will absorb the blame and protect everyone else along the chain of command from the complete impact of accountability.

In an essay, Smith wrote that the “lowest-paid person” shouldn’t be “saddled with this responsibility,” and neither should “the highest-paid person.” As an alternative, she told me, the responsibility must be spread amongst everyone involved, and the introduction of AI shouldn’t change anything about that responsibility.

In practice, that is harder than it sounds. Crootof points out that even today, “there’s not an entire lot of responsibility for accidents in war.” As AI tools change into larger and more complex, and as kill chains change into shorter and more web-like, finding the fitting people accountable goes to change into an excellent more labyrinthine task.

Those that write these tools, and the businesses they work for, aren’t prone to take the autumn. Constructing AI software is a lengthy, iterative process, often drawing from open-source code, which stands at a distant remove from the actual material facts of metal piercing flesh. And barring any significant changes to US law, defense contractors are generally protected against liability anyway, says Crootof.

Any bid for accountability on the upper rungs of command, meanwhile, would likely find itself stymied by the heavy veil of presidency classification that tends to cloak most AI decision support tools and the way during which they’re used. The US Air Force has not been forthcoming about whether its AI has even seen real-world use. Shanahan says Maven’s AI models were deployed for intelligence evaluation soon after the project launched, and in 2021 the secretary of the Air Force said that “AI algorithms” had recently been applied “for the primary time to a live operational kill chain,” with an Air Force spokesperson on the time adding that these tools were available in intelligence centers across the globe “every time needed.” But Laura McAndrews, the Air Force spokesperson, saidthat actually these algorithms “weren’t applied in a live, operational kill chain” and declined to detail another algorithms that will, or may not, have been used since.

The actual story might remain shrouded for years. In 2018, the Pentagon issued a determination that exempts Project Maven from Freedom of Information requests. Last 12 months, it handed your complete program to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency,which is accountable for processing America’s vast intake of secret aerial surveillance. Responding to questions on whether the algorithms are utilized in kill chains, Robbin Brooks, an NGA spokesperson, told MIT Technology Review, “We will’t speak to specifics of how and where Maven is used.”

In a single sense, what’s latest here can be old. We routinely place our safety—indeed, our entire existence as a species—within the hands of other people. Those decision-makers defer, in turn, to machines that they don’t entirely comprehend.

In an exquisite essay on automation published in 2018, at a time when operational AI-enabled decision support was still a rarity, former Navy secretary Richard Danzig identified that if a president “decides” to order a nuclear strike, it’s going to not be because anyone has looked out the window of the Oval Office and seen enemy missiles raining down on DC but, relatively, because those missiles have been detected, tracked, and identified—one hopes appropriately—by algorithms within the air defense network.

As within the case of a commander who calls in an artillery strike on the recommendation of a chatbot, or a rifleman who pulls the trigger on the mere sight of a red bounding box, “probably the most that might be said is that ‘a human being is involved,’” Danzig wrote.

“It is a common situation in the fashionable age,” he wrote. “Human decisionmakers are riders traveling across obscured terrain with little or no ability to evaluate the powerful beasts that carry and guide them.”

There might be an alarming streak of defeatism among the many people accountable for ensuring that these beasts don’t find yourself eating us. During various conversations I had while reporting this story, my interlocutor would land on a sobering note of acquiescence to the perpetual inevitability of death and destruction that, while tragic, can’t be pinned on any single human. War is messy, technologies fail in unpredictable ways, and that’s just that.

“In warfighting,” says Bowman of Palantir, “[in] the appliance of any technology, let alone AI, there’s a point of harm that you simply’re attempting to—that you could have to simply accept, and the sport is risk reduction.”

It is feasible, though not yet demonstrated, that bringing artificial intelligence to battle may mean fewer civilian casualties, as advocates often claim. But there could possibly be a hidden cost to irrevocably conjoining human judgment and mathematical reasoning in those ultimate moments of war—a price that extends beyond an easy, utilitarian bottom line. Perhaps something just can’t be right, shouldn’t be right, about selecting the time and manner during which an individual dies the best way you hail a ride from Uber.

To a machine, this is likely to be suboptimal logic. But for certain humans, that’s the purpose. “Considered one of the features of judgment, as a human capability, is that it’s done in an open world,” says Lucy Suchman, a professor emerita of anthropology at Lancaster University, who has been writing in regards to the quandaries of human-machine interaction for 4 a long time.

The parameters of life-and-death decisions—knowing the meaning of the fresh laundry hanging from a window while also wanting your teammates to not die—are “irreducibly qualitative,” she says. The chaos and the noise and the uncertainty, the burden of what is correct and what’s incorrect within the midst of all that fury—not a whit of this might be defined in algorithmic terms. In matters of life and death, there isn’t any computationally perfect consequence. “And that’s where the moral responsibility comes from,” she says. “You’re making a judgment.”

The gunsight never pulls the trigger. The chatbot never pushes the button. But every time a machine takes on a brand new role that reduces the irreducible, we could also be stepping a bit closer to the moment when the act of killing is altogether more machine than human, when ethics becomes a formula and responsibility becomes little greater than an abstraction. If we agree that we don’t wish to let the machines take us all the best way there, ultimately we can have to ask ourselves: Where is the road?